H ighway traffic can be sobering. It’s only when you slam to a complete stop that you realize you were just driving 65 mph protected only by a painted line everyone agrees not to cross. The economy operates in a similar manner. Stay within the lines, smooth sailing. Cross the lines, things can get ugly.

Crossing the Line

The recent line our economy crossed can be found in our reserve balance. Bank reserves are the cash deposits financial institutions keep at the Federal Reserve, used both to meet daily liquidity needs and as a foundation for the Fed’s ability to manage interest rates and provide stability in times of stress. Those reserves just crossed below $3 trillion, a threshold designed, like lane markers, to keep the system moving without collision. To not grease the fear wheel, this is a natural product of quantitative tightening and helpful when the goal is to reduce inflation. However, it is clear inflation has come down and liquidity can’t get much tighter. What now?

In a textbook playbook, the Fed would slow or stop quantitative tightening and rely on its Standing Repo Facility: the emergency hose designed to supply cash when reserves run thin. Most of the time it sits idle, but when banks and dealers begin tapping it, it’s a sign the system is leaning on the Fed for liquidity. Today, October 29, the Federal Reserve's Standing Repo Facility on Wednesday recorded the highest level of usage since its launch in 2021 (source: New York Fed).

This is important because the SRF is meant to be a backstop, not a regular funding source. When activity rises in normal market conditions it shows that liquidity is tight enough that banks and dealers are turning to the Fed instead of finding cash in the market. It is no longer being used as a backstop, but a regular source for day-to-day funding.

The Other Side of the Coin

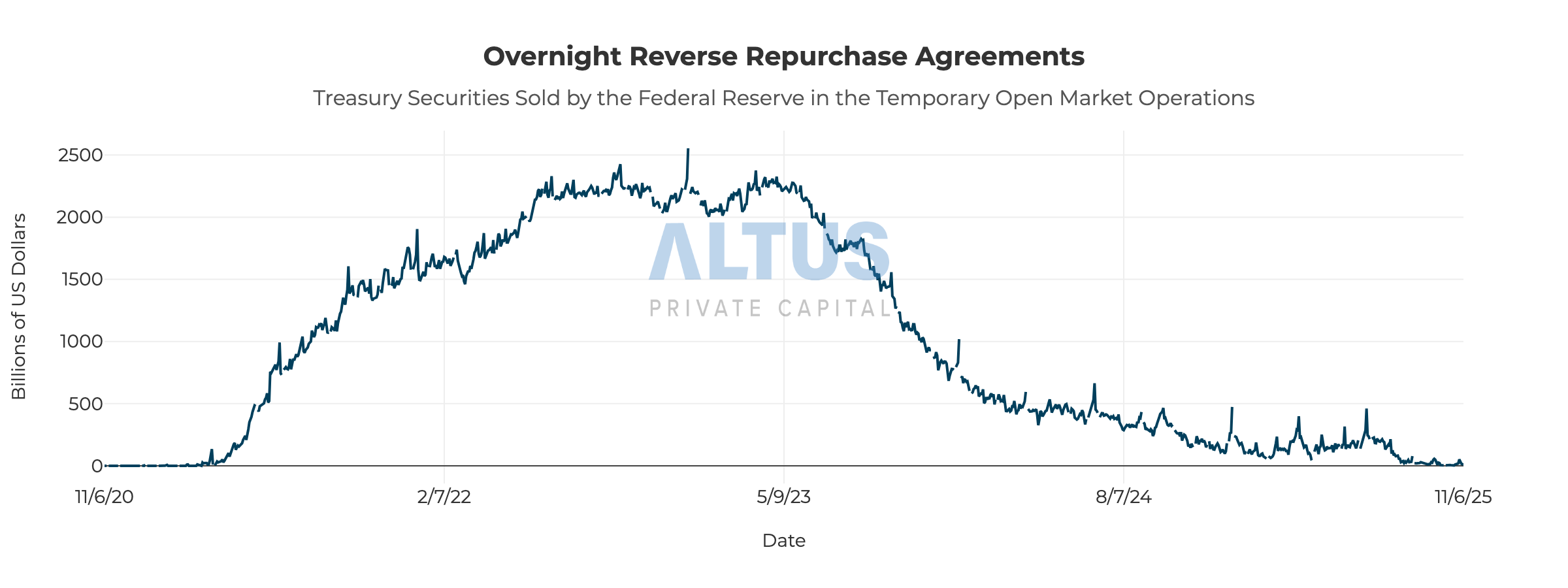

We can see confirmation of this shrinking liquidity in the balance of the Reverse Repo Facility, which unlike the Standing Repo Facility, pulls liquidity from markets when there is excess cash to stabilize growth. It came into heavy use after COVID stimulus, when trillions of dollars flooded the system and money market funds needed a safe place to park it. By lending that cash overnight to the Fed, they received Treasuries in return plus a small yield. At its peak, more than $2.5 trillion sat there.

Source: FRED

Today, that parking lot has nearly emptied, which means the cushion of “spare cash” the system once had is largely gone.

Together, the two facilities tell the story: the RRP shows the surplus cash that once flooded the system has drained away, while the SRF’s uptick shows markets are starting to lean on the Fed for funding. One reservoir is emptying just as the emergency hose is being tested. It’s not quarter-end distortion, it’s a signal that liquidity is no longer abundant.

So, if the textbook play for the Fed is to stop QT and use the SRF to ease back into growth, what’s the back up?

A Market Running Out of Cushion

Here’s where things can get concerning. The fed is only left with one option, Quantitative Easing. Why is this problematic? Because QE injects liquidity back into the system. In today’s backdrop, that means new inflationary pressure. To contain that pressure, rates would have to stay higher for longer. That’s the circle of fire: liquidity injections to stabilize the economy are followed by inflationary power that must be regulated with higher interest rates. The new fed fear is pivoting to liquidity, and private credit is showing its first cracks.

Tricolor, a subprime auto lender, collapsed almost overnight, followed quickly by First Brands, an auto parts supplier buried under nearly $10 billion in disclosed and undisclosed debt. Off-balance sheet financing, multiple layers of rehypothecated receivables, and opaque trade finance structures left creditors and funds from UBS to Millennium and Jefferies facing billions in losses. What looked like steady yield unraveled into defaults.

The damage hasn’t stopped there. Regional banks are now reporting losses tied to bankruptcies and fraud, with Zions and Western Alliance disclosing charge-offs and Jefferies sliding on exposure to First Brands. Auto loan delinquencies have surged 50%, hitting not only subprime but also prime borrowers as high car prices, longer loan terms, and interest rates above 9% push households upside-down on their loans.

The Road Ahead

What does this mean for markets?

As of now, it’s all quiet on the western front. However, OPEX cleared substantial positive gamma for equities, leaving negative gamma and room for amplified price behavior and volatility. With no shortage of catalysts… (liquidity, tariff talk, government shutdown, rate cuts, earnings) it’s likely October will live up to its volatile name.